On a rainy Bucharest night in 1970, Elena Oprea, a waitress, was making her way home from her shift. Entering the courtyard of her housing block at around 2am she heard footsteps behind her in the darkness, and a man’s voice. She screamed and was struck by a metal rod across the head. Elena was stabbed several times and cried for help as she was bludgeoned to the floor. Neighbours, woken by the commotion, eventually dragged her inside and called an ambulance as the attacker made off into the night. Hours later she was dead.

Elena was the first victim of Ion Rimaru, Romania’s most notorious serial killer. He would go on to attack 14 more women before he was eventually caught. Four were killed, many were raped, others were mutilated. In some cases he ate their flesh – biting out their genitalia and sucking their blood.

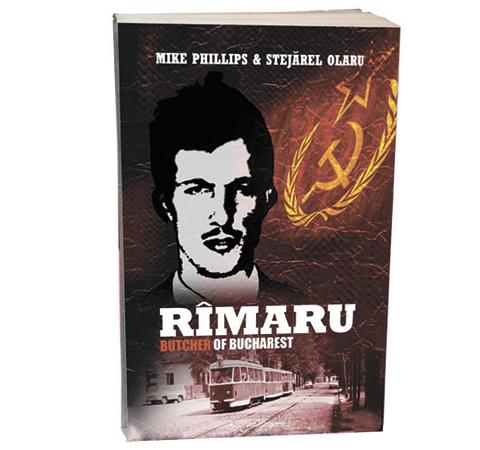

But how did he evade capture for so long? A new book by Haringey author Dr Mike Phillips, Rimaru: The Butcher of Bucharest, suggests the communist regime of the era, a state-ruled media and the inefficiencies of the authorities helped create a ’perfect storm’ in which Rimaru’s evil could flourish.

“He was disturbed, mad even, but by and large most of the society tried not to notice,“ says Mike, who along with co-author Stejarel Olaru gained unprecedented access to police and secret police records, including the testimonies of the killer and his family for the book. “It tells you a number of things about the authorities of that time, about the relative ignorance about psychiatric conditions and you have to remember he was a proletarian, you have to read it in those terms. He came from healthy proletarian origins, from rural peasant stock and everyone in the society was bending over backwards to accommodate people like that.“

By the time he attacked his second victim, Florica Marcu, who was knocked unconscious outside her home and dragged to a cemetery where she was raped, stabbed and had her blood sucked, rumours were already circulating the streets. There was a vampire in the night, a bloodthirsty killer on the loose. But the newspapers didn’t cover the story at all.

“The state-ruled media was full of propaganda,“ explains Mike, “and the censorship did not encourage articles about criminals and law breaking – it was considered that in a socialist society there were no crimes and no criminals, or at least such events were rare and not done by the working people.

“There was denial it was going on.“

This, coupled with the reluctance of citizens to talk to the police, meant Rimaru evaded capture for many months.

“There was a reluctance for people to get involved in things that did not concern them directly, especially when that might lead to further involvement with the authorities.“

As a child, Rimaru had shown signs of violent behaviour and his childhood had been troubled, which is documented in the book – but his tendencies were never noted or taken notice of.

“He was given to violent outbursts,“ explains Mike, “he was known to torment and kill small animals. But the ideology of the regime simply did not allow for the idea that the perfect socialist state could be the incubator of mental illness – these people could only exist in countries of capitalist decadence!“

Through the sterling detective work of an out-of-town Militia (Police) Colonel, who is tracked down and interviewed in the book, Rimaru was eventually brought to justice but his story, though rarely talked about in Romania, was not quickly forgotten.

.jskwjjjioRimaru: The Butcher of Bucharest is a fascinating read, full of detail, that frames a factual account of the crimes within their social environment, while examining their impact on the culture, and their lingering legacy in the present day.

Rimaru: The Butcher of Bucharest is available from all good bookshops and online at: profusion.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here