As Tottenham's residents and business owners rebuild following the riots that raged there earlier this year, questions continue to ring in their minds - why did this all happen? How can we stop it happening again?

The same questions were being asked 26 years ago just a short walk from the site of August's destruction, at Broadwater Farm, a huge estate of more than 1,000 flats straddling the River Moselle, which saw civil unrest boil over after a, at first, peaceful protest.

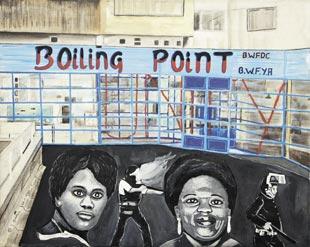

With his exhibition, Broadwater Farm: The Story of a Community 1967 - 2010, open now at Bruce Castle Museum, social historian Odin Biddulph sits down to explain what really happened on that fateful day and the incredible work that has gone on to make the modern Broadwater Farm a model of social housing with one of the lowest crime rates of any urban area in the world.

What inspired you to stage the exhibition in the first place?

I live in the area with my girlfriend and our three children, go to Lordship Rec, use the community and health centre on Broadwater Farm, go to the local museum with my family and noticed that unless you already knew about Broadwater Farm you’d have no idea it ever existed. I wanted to open its history up to the whole community.

Unlike Brixton, there has been a complete cultural void in Tottenham in terms of talking about the disturbances at Broadwater Farm in 1985 and I felt there was a need to address that and allow people to talk about it.

I also noticed that there was a myth that Tottenham had become run down following the disturbances at Broadwater Farm in 1985, despite the fact that it had been a deprived area for many years prior to that. And there seemed to be a danger of making what happened at Broadwater Farm into a race issue and then blaming all of Tottenham’s woes on one section of the community despite the fact that there many different races involved. When people look at Tottenham they seem to forget about the failure of local manufacturing, large scale unemployment, the creation of Wood Green Shopping City and the impact that had on shops and businesses on Tottenham High Road - they also forget about the impact of Tottenham Football Club which has killed off half of the High Road for at least ten years while they wait to redevelop their stadium. There is also a complete amnesia about the effect of football violence, in terms of shutters on shop windows and fears for security – which became an international issue - not that long ago, and the amount of resources needed to police those games nowadays.

What appealed to you about the area and its story?

I was really inspired by the Hollywood style heroism of what the community was doing before the disturbances to turn the estate around - and the exhibition is a testament to the courage and the commitment of the community in bringing about change and their struggle to continue to fight for change in the ferocious aftermath of the riot.

How well had Broadwater’s history already been documented?

Broadwater Farm’s history has been quite well written about and it has been the focus of many academic studies and documentaries over the years, but there was very little evidence of this locally, especially in the recent local history books covering Tottenham or in the local museum – which all presented the same black and white photograph of ye olde original Broadwater dairy Farm. There was also very little visual material available of how the estate used to look or of what was going on before the uprising.

People were amazed to see a TV programme focusing on the successes of the Youth Association and its founder Dolly Kiffin dating back to 1984, a year before the unrest. At point Dolly Kiffin actually says something like the youth need employment and opportunities otherwise there well be a riot’. The Neighbourhood office and community leaders have been telling the story of the Youth Association for more than two decades and their jaws literally dropped as they saw the video for the first time.

Was it easy to gather stories from residents? What was the most challenging part of gathering material?

People really wanted to tell their stories not only from Broadwater Farm but also from the surrounding area – people also had a need to talk about the disturbances and also those who had been involved in the estate over the years and helped to move things forward. I could have included a lot more about how passionately people still feel about those events. One person told me that ‘if you treat people like dogs, don’t be surprised if they come up and bite you’ and I wish I’d allowed more of people’s raw feelings to come through in the exhibition panels.

The greatest challenge was earning trust and respect from members of the community who have a history of being ill-treated by the media over the years.

What were you expecting to find? Did you find anything that really surprised you?

The story of the Youth Association completely stunned me because here was the story of the community before the unrest brought back to life on the screen.

I’m still greatly moved by video showing the opening of the Garden of Remembrance for all those who suffered on the 5th and 6th of October 1985. The force of what people were still feeling in the community and from local government three years after the unrest and their courage to struggle on and their determination to move forward is still incredibly powerful today, 26 years later.

What would you say was most to blame for the riots there?

There were many factors involved, the first to remember is that people were calling on the Police to suspend the officers involved on an illegal raid of Mrs Cynthia Jarrett’s home during which she died. But the Independent Inquiry, chaired by Lord Gifford QC, highlighted poor policing, on-going suspicion between the ‘black community’, the youth and the police. While the Inquiry praised the efforts of the Youth Association in making significant inroads, it pointed out that there were inadequate amenities on the estate itself, which many felt was like living in a prison and highlighted poor education, mass unemployment, alienation of the youth, marginalisation, social exclusion, and institutional racism. Lastly, there was a failure to heed the recommendations made after the Brixton Riots of 1981 by Lord Scarman.

However, there is still a strong feeling, by many who were around at the time, that police tactics played a major part in sparking the disturbances and then fanning the flames of discontent, by not letting protesters, on their way from the police station to the Afro-Caribbean Centre in Hornsey, off the estate. Everyone has said that once the unrest started, there were as many ways to stop it as there were entrances onto the estate, but the police held back. Many think the police hemmed people into Broadwater Farm, in what we know call a kettling tactic, to stop any potential risk to Wood Green Shopping City.

Did the design of the buildings contribute?

The bleak bare concrete design, cut off from the rest of the community, with its lack of facilities and opportunities, may have played a part in fuelling the alienation of the young people living there, who might have been involved- but people were coming and going off the estate all night.

Who should be praised for the area’s complete turnaround? How has it become such a success?

Everyone from the community to the council played their part in turning the estate around- but without the achievements of the Youth Association – founded by Dolly Kiffin and Clasford Stirling, MBE, dating back to 1981, when they kicked the doors off of an abandoned chip shop in Tangmere Block to make it their youth club, it’s hard to know whether the whole estate would have been raised to the ground after the disturbances – notwithstanding the fact that the community was passionate that they wanted to stay where they were, but wanted better amenities and facilities.

The violent civil unrest that exploded on Broadwater Farm in 1985 seriously highlighted the issues that the community had been trying to voice for years and made everyone stop and think about what kind of future they wanted. The subsequent Inquiry revealed the terrible conditions that people had been living in and what needed to be addressed.

In the absence of any serious local recent history in Tottenham, it looks like we’ll have to await a similar Inquiry.

Are commentators right to draw comparisons between the Broadwater Farm riots and the recent troubles nearby earlier this year?

The similarities between 1985 and August 2011 are so clear – in terms of the way the police handled the situation that you have to wonder had we seriously engaged with our past whether we could have avoided the destruction of the present. But for some reason, the council and local historians seem to have thought it was best not to talk about the past.

It’s worth remembering that Broadwater Farm today is respected as a model of social housing. Many estates in Tottenham and the rest of the country could benefit greatly by what has been achieved at Broadwater Farm. But this requires the commitment of the community and government to bring about that change.

You also have to remember that the civil unrest at BWF continued for many hours after a policeman was killed and on into the early hours of the morning. People felt they were either defending their homes, their freedom or their rights as human beings. There was a real sense of injustice at the way things were back then, and things were bad.

Today, Tottenham has one was the largest youth unemployment in the country, many people who can, move out of the area before their children reach secondary school, and the riots of August took place at a time when youth clubs were being dismantled and people were scared for their future. Saying all that, it’s hard to imagine the High Road burning down without the tragic shooting of Mark Duggan and the failure of the police and the IPCC to engage in any meaningful way with his family and the wider community in the days that followed.

What was the reaction to the original exhibition at Broadwater Farm?

It’s an incredibly intense and powerful story, even without the night of civil unrest that, many visitors were changed people when they walked out of the exhibition at the community centre.

Many people used the exhibition space to tell their own story – what I’d left out or about the many challenges still facing their communities today, even people who don’t live on BWF. Visitors were absolutely amazed and overwhelmed that their history should be up on the walls at all and treated with such care and attention. They were amazed and moved by the video material, both of the youth association, a clip from panorama going back to 1983 showing problems with the police and showing the opening of the Garden of Remembrance which allowed them to mourn for all those who suffered both during and after those events.

How did its presentation at Bruce Castle come about? What do you hope the exhibition will achieve there?

I hope people will come away with a deeper understanding of the history Broadwater Farm, and the context in which the disturbances took place but also to experience the bigger Broadwater Farm story with all its heroes and homemakers.

There’s been such an overwhelmingly positive feedback - but I put the whole thing together on a shoestring of just £700 and I’m looking at ways to raise funds to develop the exhibition further with the community give this part of London’s history the attention it deserves. In many ways the history of Broadwater Farm is the history of Tottenham and I hope to bring that story to the wider world.

Broadwater Farm: The Story of a Community 1967 - 2010 is at Bruce Castle Museum, Lordship Lane until March 2012. Details: 020 8808 8772 www.broadwaterfarm.info

A book about the Farm, a visual record with personal accounts of the life, history and culture of one of London's most vibrant communities by Odin Biddulph is due for release soon.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article